Humans are born to squat: Infants do it. Athletes do it. In some parts of the world, adults do it while conversing or working, sometimes for hours on end.

But in first-world countries, most of us stop squatting when we reach adulthood, and that’s a shame, because the parallel squat is one of the most effective, functional movements you can do, bar none.

It strengthens your legs and glutes, mobilizes your hips and ankles, and improves overall power and athleticism.

There are, however, a surprising number of ways to screw up this seemingly simple movement.

Read on for how to do a proper parallel squat, every time.

Parallel Squat: Step-by-Step Instructions

Most of us squat to sit multiple times a day but that doesn’t mean we’re always doing it properly. Here’s how to use correct form when you’re parallel squatting in the gym:

- Stand with your feet between hip and shoulder width apart, toes pointed forward (slightly pointed out is OK too), arms extended in front of you.

- Keeping your chest up, gaze forward, feet flat, and your lower back in its natural arch, bend at your hips and knees until your thighs are parallel to the floor. Your knees should be tracking in line with the middle of your feet.

- Pause, and return to the starting position.

What Is Considered a Parallel Squat?

A true parallel squat is one where the exerciser lowers their hips until the tops of their thighs are parallel to the floor while keeping their lower back flat and their chest up.

The parallel position is lower than you think, and most people — even longtime lifters — stop a few inches short of a true parallel position.

One cue: Think of lowering your hips until the crease of the hip is just slightly lower than your knees.

Made it? That’s parallel. Anything less isn’t.

Common Mistakes on the Parallel Squat and How to Fix Them

1. Too much weight

Many exercisers put a bar on their back before they’ve mastered the bodyweight version of the move. That’s asking for injury.

How do you know if you’re using too much weight? As you descend into the squat, “You want a parallel line between your shins and your spine,” says Cody Braun, CSCS.

Seen from the side, in other words, your torso shouldn’t pitch forward more than your lower legs.

If that happens (film yourself or have a buddy check your form), take some weight off the bar, or ditch the bar altogether, and build up gradually from there, using picture perfect form on every rep.

2. Poor form due to lack of mobility

Other problems that arise on the parallel squat aren’t due to lack of strength but lack of mobility.

Since most of us sit in chairs rather than on the floor, we lack the ankle- and hip-mobility needed to sink all the way to the parallel position.

As a result, many people compromise squat form by rounding their lower back (instead of keeping it slightly arched), raising their heels (instead of keeping them flat on the floor), or collapsing their knees inward (instead of tracking in line with the middle of the foot) as they rise from the squat.

Here are a few solutions to try:

Heels-Elevated Squats

Place a pair of ten-pound weight plates (or a board up to an inch-thick) underneath your heels.

This simple trick frees up the ankles, allowing most people to parallel squat without limitation or pain. This is a good tip to use when teaching or learning the bodyweight squat.

However, you should be aggressively working on other exercises that help increase ankle mobility.

Suspension Trainer Squat

Lean back while holding the handles of a TRX (or equivalent). This modification activates the extensor muscles of the spine, helping you to keep the torso upright throughout the move.

This also helps people sit back lower into the squat because of the counterbalance for weak glutes.

Still struggling?

Perform either or both modifications to the depth you can accomplish with good form, and without pain.

Over time, you’ll develop the mobility and strength you need to squat deeply.

Can’t make parallel? Don’t force it — just go with the depth you have.

Parallel Squat Variations

Once you’ve mastered the parallel squat using your bodyweight (15 to 20 reps is a good target rep range for the beginner), you can start adding weight to the movement, first with a dumbbell held vertical in front of your chest (a goblet squat), then with a pair of dumbbells at your sides, and finally, if you choose to, with barbell back or front squats.

Add weight slowly over time — and don’t lose the depth you developed while performing parallel bodyweight squats.

Are Parallel Squats Effective?

“Squats are one of the best exercises for assessing how the body moves, because it relates to everyday movement, and requires the entire body to be active,” says Braun. “It is also a great full body exercise.”

Some lifters swear by heavy barbell squats as the ultimate leg-builder; for others, they’re primarily a source of joint and back pain.

So keep the bodyweight version in your rotation — as a warm-up, a thigh-building exercise, or both — but evaluate your own response to barbell varieties.

If the move leaves you with painful knees or a bad back for days on end — have a trainer or physical therapist look at your form.

No pain or problems? Full speed ahead.

What Muscles Do Parallel Squats Work?

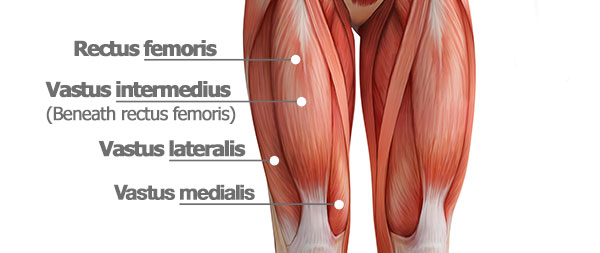

Parallel squats are a terrific all around lower-body movement, focusing primarily on your front thighs (quadriceps), which extend your legs at the knee joint, and your glutes (butt muscles), which extend your hips.

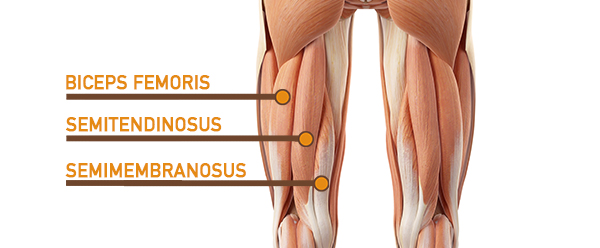

Secondary players include your hamstrings (back-of-thigh muscles), which help with hip extension, and the core muscles of your lower back and abdomen, which provide stability throughout the move.